Conversations in Landscape Painting

A long, long time ago, on a crisp,

cool morning, I sat outside, breathed in the clean Vermont air and proceeded to

paint the World's Worst Painting. Ever.

Before this momentous occasion, I

had been making art-type stuff for a couple of decades. I adored figure

drawing, mixed media and dabbled in the 3-d, creating life size paper mâché

figures that populated my home like drunken party guests who never leave.

I had supported my habit and

education with a line of low-paying, but rewarding jobs. (me in a job

interview: "of course, I can do that

thing you just said. I have lots of experience at that thing you just

said.")

That interview technique led me to

stints as a magazine editor, bartender, gallery curator, newspaper illustrator,

lifeguard, theater creative director, set designer in Moscow, Russia, TV

broadcast designer, courtroom artist, and teacher.

Mostly teacher.

I found teaching to require as

much cunning as any painting on canvas. Never just a means of support,

teaching continues to be the way, I hope, I may leave a small impact. I

continue to teach Art History at UNCC, workshops at Ciel Gallery and lead

groups of painters to Italy every year.

Later, I loved every minute of

being a student at NCSU, ECU and James Madison University where I maintain a

vague memory of professors dismissing landscape painting as a hackneyed subject

whose hay day happened several chapters back in the Big Book of Art.

However, on that Vermont day, I

pushed those memories aside and for the first time, at the urging of my friend,

set out to paint "on location." I gathered my paints in a

plastic Harris Teeter bag, found a plate for a palette and perched on a rock

next to my friend, Kathy (who, greatly experienced at this art form, used a

Julian easel exactly like Van Gogh's).

"Just shut up and

paint," was the only advice I got that day.

After some red, green (lots and

lots of green) and mountains that looked like piles of boiled spinach, I had my

creation; along with a sunburn and a few "I swear to god, a bug

just crawled up my shorts!" moments. But more importantly, I

experienced a sensation of having just absorbed my surroundings in a more

intense way than I ever had before. I felt a connection to

everything around me that went far deeper than merely observing.

But the painting? A smart person

would have recycled their Harris Teeter bag with the painting in it. But

I was not that smart person and I continue to be grateful to my friend who not

only introduced me to landscape painting, but who also conveniently neglected

to tell me just how teeth-grindingly, gawd-awful my painting was. Twenty

years later and she's still biting her tongue.

It didn't matter. I was

hooked. And I was persistent.

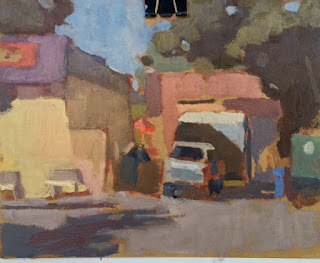

Since then, plein air painting has

served as my classroom. Like the Barbizon painters, it is where I study,

challenge, learn to see and enjoy a real conversation with nature.

A chat sounds like this:

"How dark does that shadow want to be?"

"Is that tree trying to overwhelm the house beside

it? protect it? dance with it?"

"This sandy road is happy to share bits of orange

with those trees."

I confess to almost a workman type

approach to condensing what is before me. "Eliminate

the obvious, exaggerate the essential" (Van Gogh). All this while

striving to paint in a way that suggests energy, spontaneity and life.

This is not unlike the dancer who works for years just to make a beautiful leap

look easy.

I've been so humbled and fortunate

to receive awards, exhibitions, and recognition for my work, both in plein air

and my studio paintings. I'm especially happy to be a part of the Ciel Gallery

family. (I tell people that "the energy at this gallery forces me to pedal

harder!").

But my secret is that ever since

Vermont, landscape painting has never become the "effortless leap"

for me. Each painting is a new puzzle. But I hope to happily spend

all my years not quite 'figuring it out,' and looking forward to our next,

imperfect, conversation.

But my secret is that ever since

Vermont, landscape painting has never become the "effortless leap"

for me. Each painting is a new puzzle. But I hope to happily spend

all my years not quite 'figuring it out,' and looking forward to our next,

imperfect, conversation.

www.jeancauthen.blogspot.com

Comments

Post a Comment